A mental image of another being may appear,

of a being less fortunate.

Many attempts have been made to portray this,

but we are not that being.

Throughout history we have written of glories, of joys,

of certain harmonies.

But each of us, live in ways that allow us to ignore what we are not.

We the fortunate often live wrapped in our own stories.

Often we forget that things can get worse.

Or perhaps we see our apparent separation

as a justification for selfishness.

Thus, for hundreds of thousands of years,

human beings have committed countless acts of cruelty.

Thus we have ignored innumerable experiences of others.

But sometimes, in our minds,

a space opens for considering the other.

Perhaps starting with those close to us,

but often expanding further and further

toward what may not be so familiar.

How beautiful that is: human compassion.

Sometimes we see it in properly ethical medicine, in veterinary care;

sometimes in meditation,

sometimes in an attitude or a conversation,

sometimes in an initiative or a religion.

How beautiful it is when it overwhelms us,

when it truly and deeply moves us,

when it has no limits.

How beautiful it is when it manages to change opinions,

when it listens to science and logic.

And when it listens to science and logic,

it then notices tremendous magnitudes,

the true scale of what is ethically valuable.

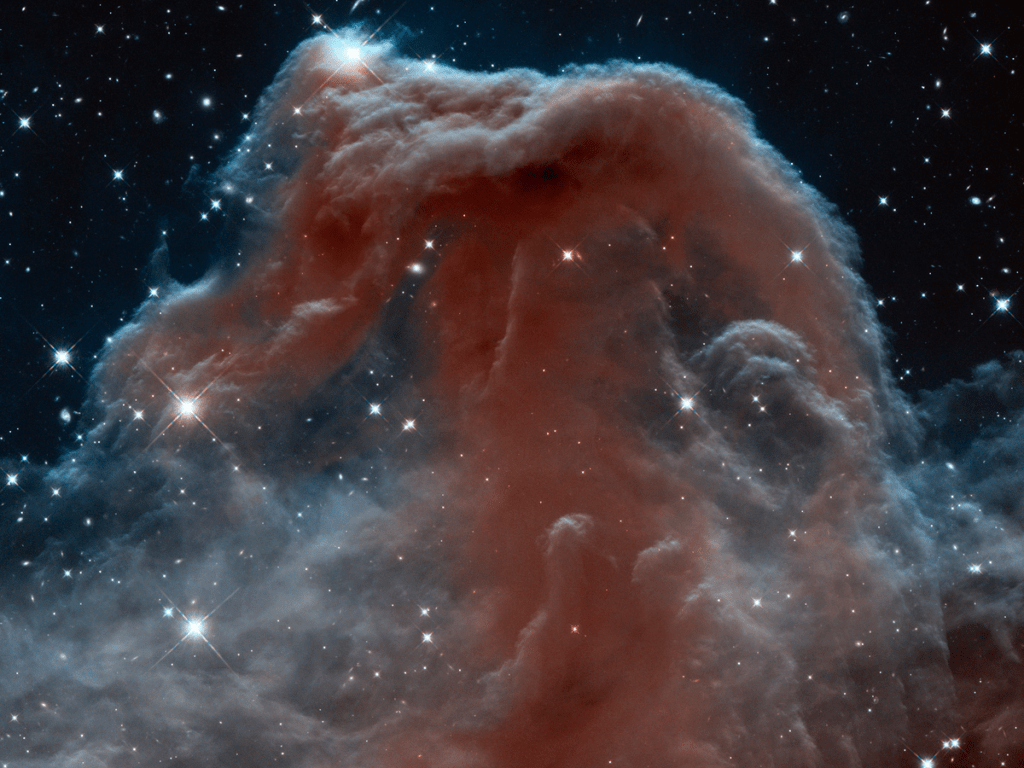

Imagining a stone against the entire Himalayas.

-

No hay comentarios en In compassion

-

Puede aparecer una imagen mental de otro ser,

de otro ser menos afortunado.

Muchos intentos se han hecho para retratar esto mismo,

pero no somos ese ser.Durante la historia hemos escrito de glorias, de penas, de alegrías,

de ciertas armonías.

Pero nosotros, quienes habitamos otros reinos, vivimos de formas que nos permiten ignorar lo ajeno.Los afortunados vivimos muchas veces envueltos en nuestras propias historias.

Muchas veces no recordamos que puede ponerse peor.

O tal vez miramos nuestra separación aparente

como una justificación del egoísmo.Así, durante cientos de miles de años,

los seres humanos hemos cometido innumerables actos de crueldad.

Así hemos ignorado incontables experiencias ajenas.Pero a veces, en nuestras mentes,

se abre un espacio para la consideración del otro.

Tal vez empezando con las personas cercanas a nosotros,

pero muchas veces expandiéndonos más y más

hacia lo que tal vez no sea tan familiar.Qué cosa tan bella es esa: la compasión humana.

A veces la vemos en la medicina apropiada, en la veterinaria;

a veces en una meditación,

a veces en una actitud o una conversación,

a veces en una iniciativa o una religión.Qué bella es cuando nos sobrepasa,

cuando verdadera y profundamente nos mueve,

cuando no tiene límites.Qué bella es cuando logra cambiar los pareceres,

cuando escucha a la ciencia y a la lógica.Y cuando escucha a la ciencia y a la lógica,

entonces nota tremendas magnitudes,

el verdadero tamaño de lo éticamente valioso.El imaginar una piedra en contra de todo el Himalaya.

-

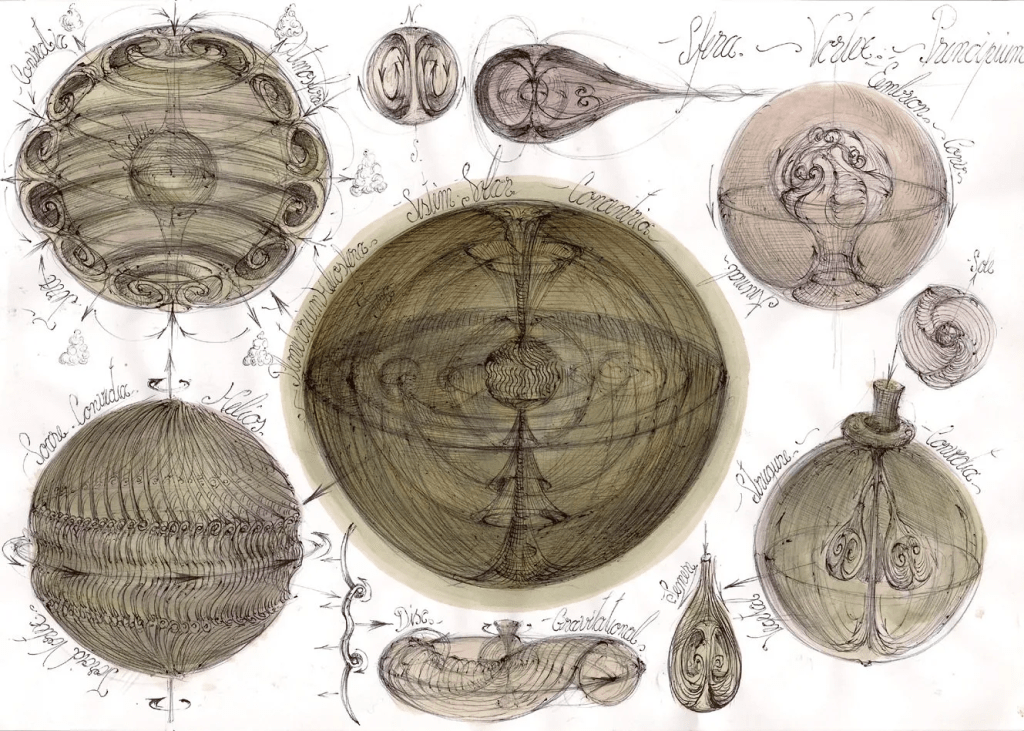

Sobre aquello en lo que nos fijamos, sobre qué es valioso, los objetos intencionales y las tiranías.

Hoy voy a hablar de qué es el valor y de qué es valioso.

La vida darwiniana en la tierra tiende en muchos casos a ser un proceso muy cruel, donde existen grandes cantidades de sufrimiento.

¿Qué se siente ser diferentes animales?

Seguramente el león pensará en qué comer.

¿Se sentirá libertad al volar como un ave?

Las ballenas seguramente viven en un mundo construido en base a su ecolocalización.

Algunos animales viven aterrorizados escapando, otros están sufriendo intensamente.

Los seres humanos compartimos mucho con otros animales y a la vez tenemos un lado intelectual y racional.

Todos los animales tenemos tendencias o fijaciones y estas nos mueven.

Pero existen contradicciones entre lo que diferentes animales consideramos valioso, diferentes “observadores” “observan” (notar las comillas, dejadas ahí para dejar un cuestionamiento sobre qué son los observadores) la misma situación de diferentes maneras. Entonces…

…¿Existe algo realmente valioso?

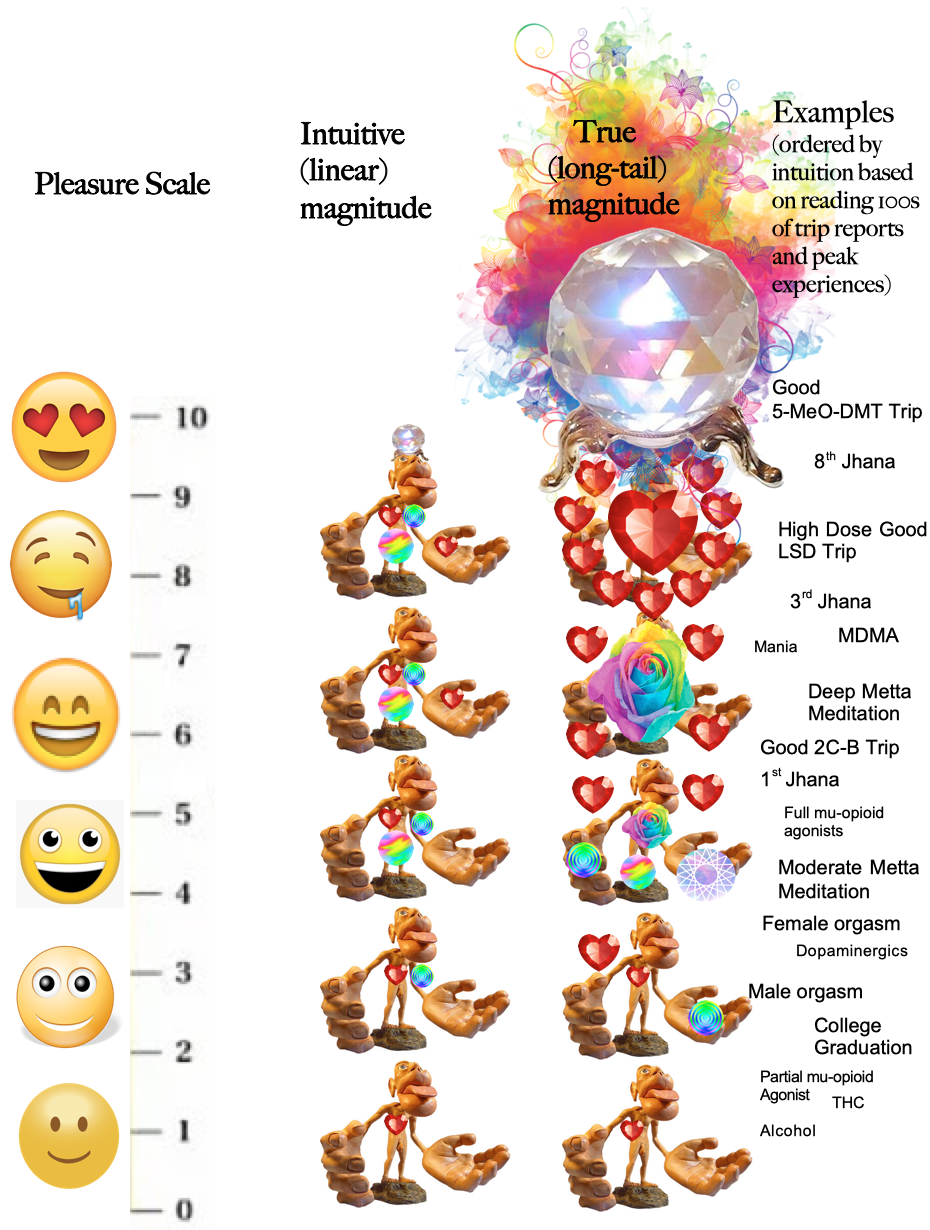

Desde la perspectiva del animal agonizante, su sufrimiento es verdadera e intensamente horrible, independiente de lo que cualquier otro ser pueda pensar, de la misma manera, el éxtasis profundo de un jhana es real.

De una manera se puede argumentar que todo el sufrimiento del universo es en realidad, «nuestro» (¿o es el nuestro «suyo»? ¿Hay realmente un yo?)

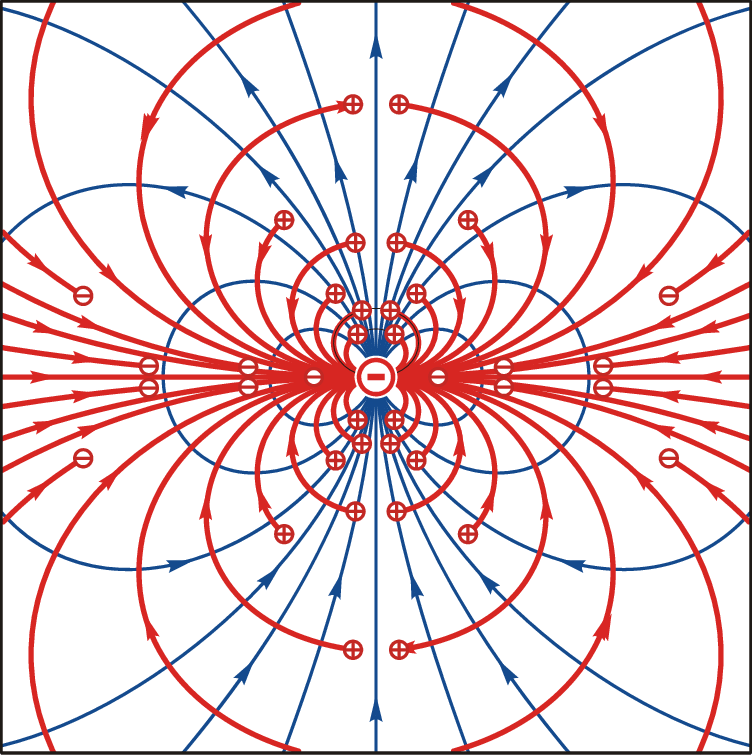

La física nos ha enseñado a ver la(s) «cosa(s)» como campo(s).

¿Y qué es el valor en estas experiencias?

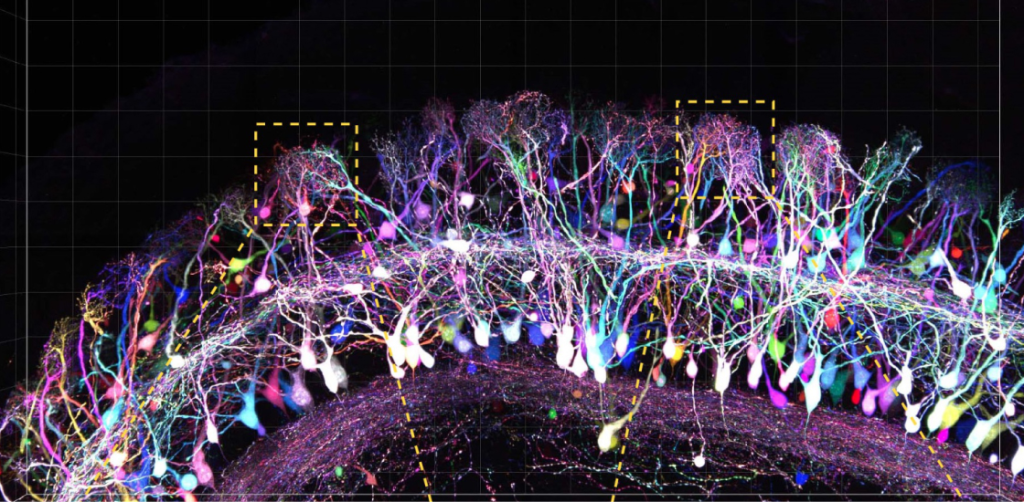

Hemos tratado de entender la naturaleza del placer y del dolor de muchas maneras, la hemos relacionado, por ejemplo, con la activación de diferentes áreas del cerebro, el área tegmental ventral para el placer y el giro cingulado para el dolor son algunas de las que hemos encontrado.

Se ha notado que cuando experimentamos cosas que inducen sensaciones de bienestar o malestar, se activan estas áreas.

En el síndrome de Geshwind, un tipo de epilepsia de lóbulo temporal, las personas tienen experiencias extremadamente profundas y hermosas, que tienden a conducir a la hipergrafía, la hiperreligiosidad y a experiencias espirituales profundas. Todo esto explicado por una actividad neuronal anormal que se tiende a atribuir a otras causas.

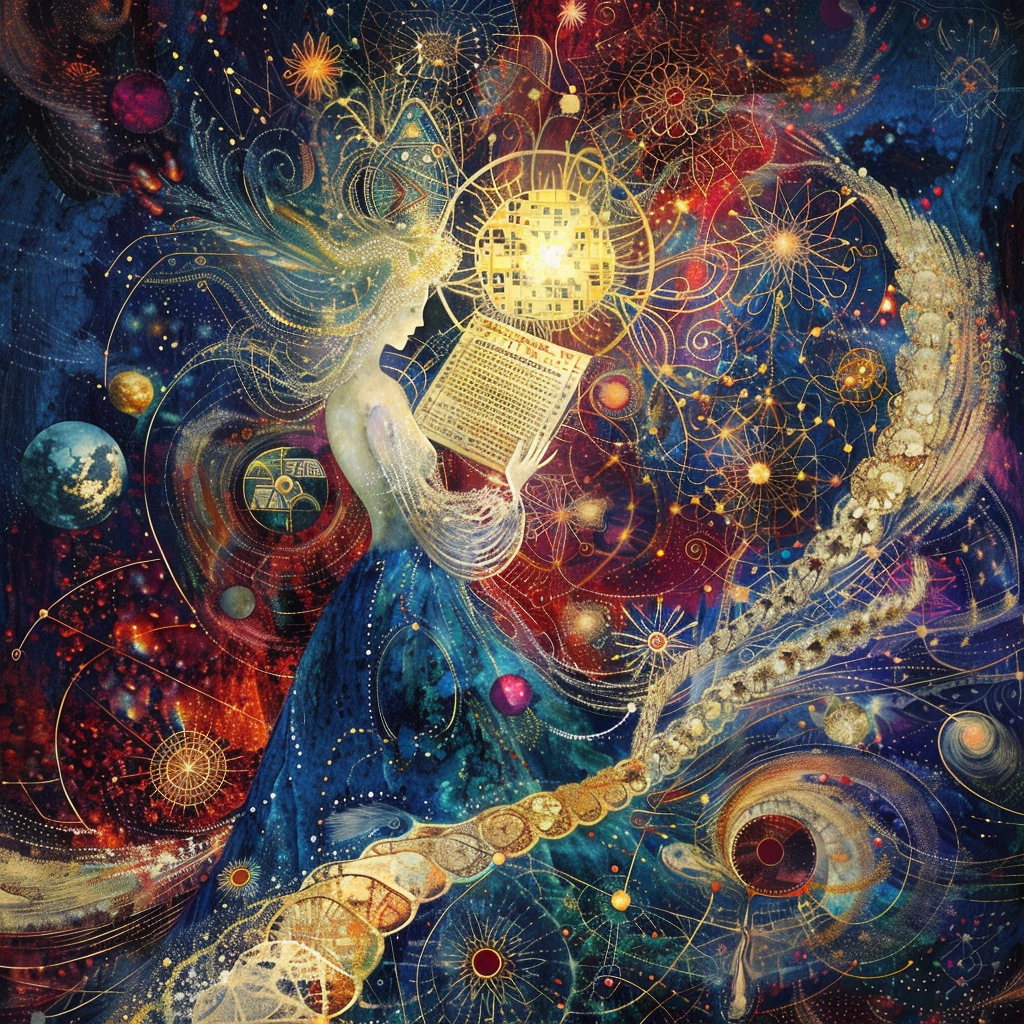

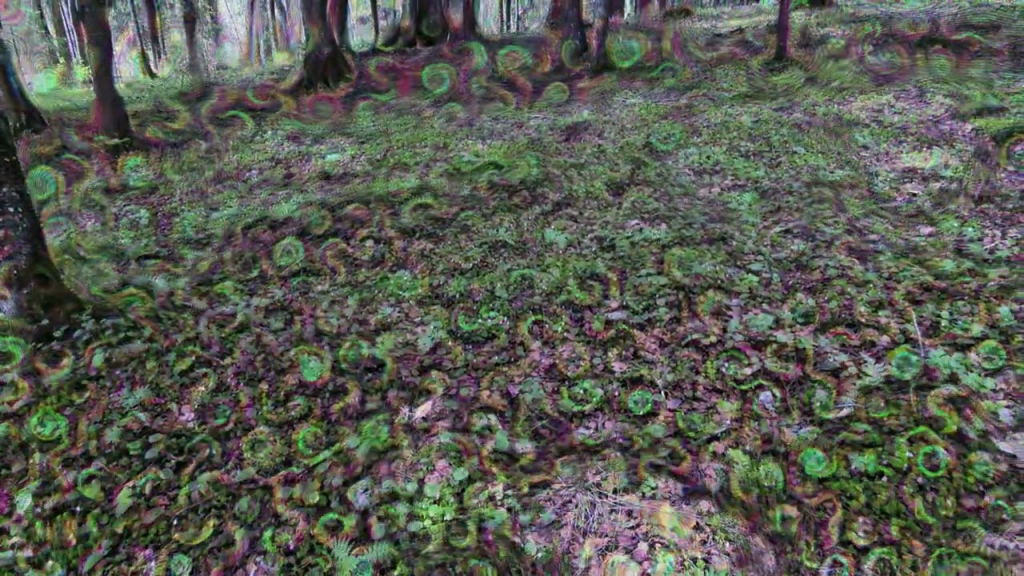

Para entender el mundo de una manera adecuada, una de las ideas más relevantes es la del realismo indirecto de la percepción, aquello que experimentamos no es directamente el mundo externo (cf. realismo directo) sino una representación o simulación dentro de nuestras cabezas, una especie de diorama, basado en este mismo. Para hacernos una imagen de este concepto, podemos imaginar una especie de burbuja hecha de qualia que toma la forma de un mundo (aquí hablo más en detalle sobre este concepto). También a nuestra experiencia se aplica el realismo indirecto de la valencia, las cosas que percibimos como valiosas no lo son directamente, sino que su representación tiene una valencia.

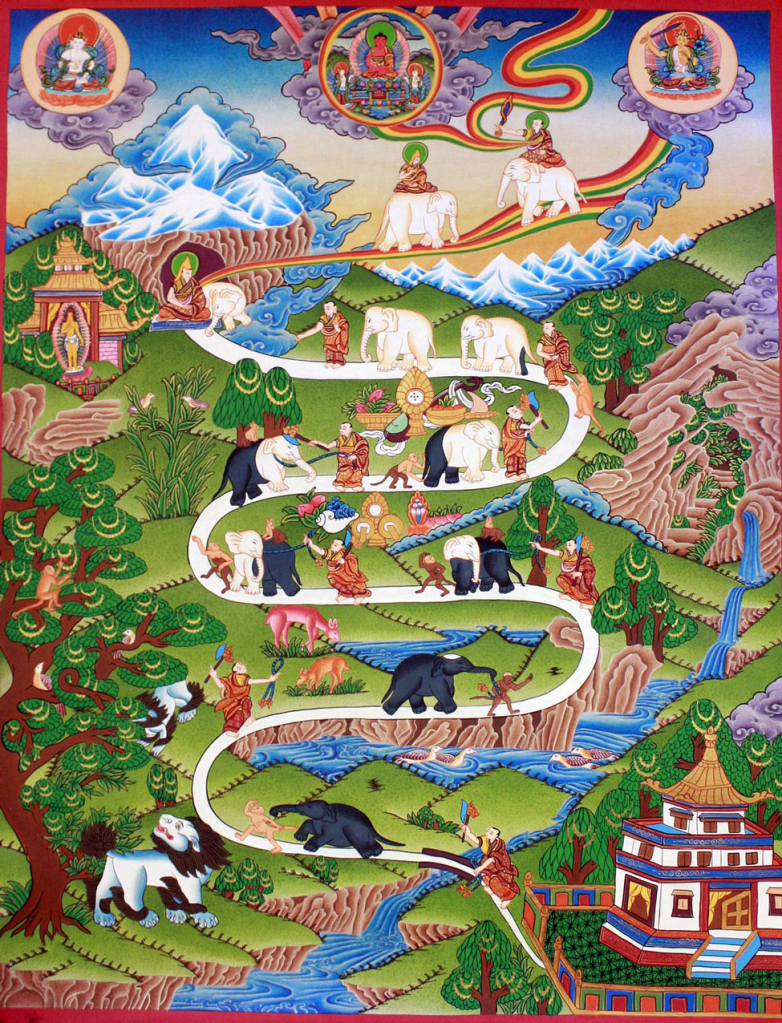

Así nuestras representaciones tienen apariencias que no necesariamente reflejan el mundo externo. Por eso podríamos decir, los budistas hablan de una existencia cíclica en reinos de fijaciones, que forman una aparencia ficticia de la realidad desde su interior y por eso una de las tres marcas de la existencia según ellos es la insatisfactoriedad.

Cada experiencia tiene una determinada valencia, existe la valencia positiva, como la alegría, la negativa como la que tiene el dolor, está la mezclada, podemos sentir valencia positiva y negativa a la vez, o existe la neutral.

La valencia es interpretada usualmente de maneras diferentes a «esto es valencia» por nuestra experiencia. Aunque lo que está sucediendo en realidad es que hay representaciones, las cuales tienen diferentes valencias, se suele pensar que lo que activa diferentes estados de valencia es directamente bueno o malo.

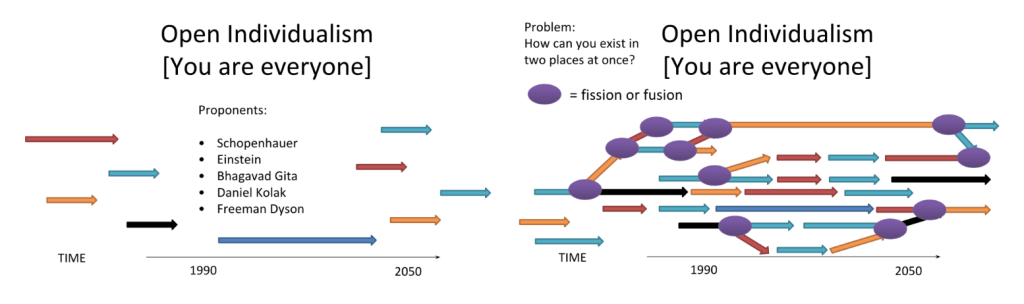

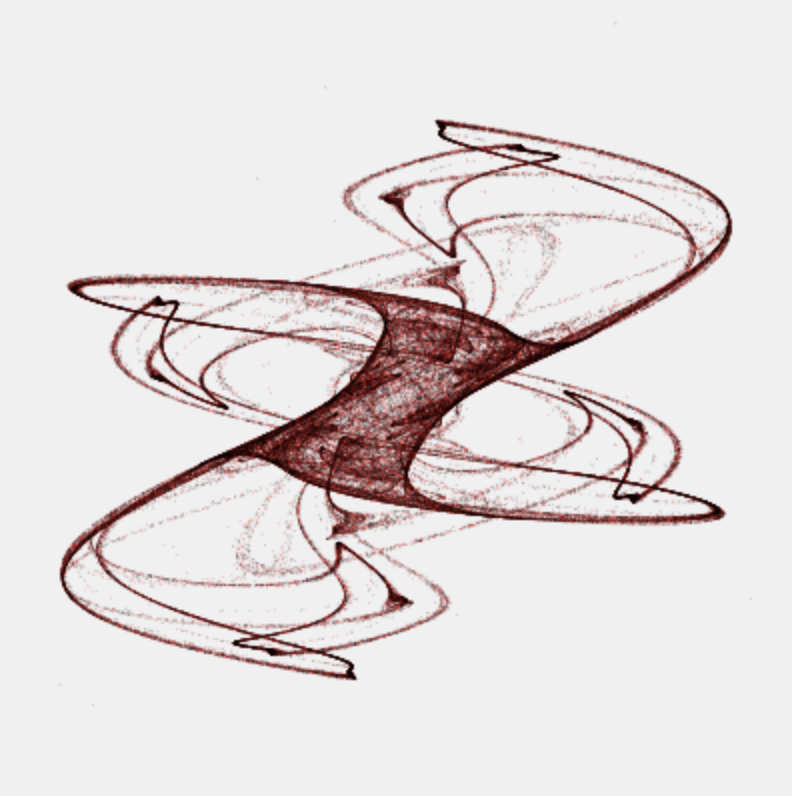

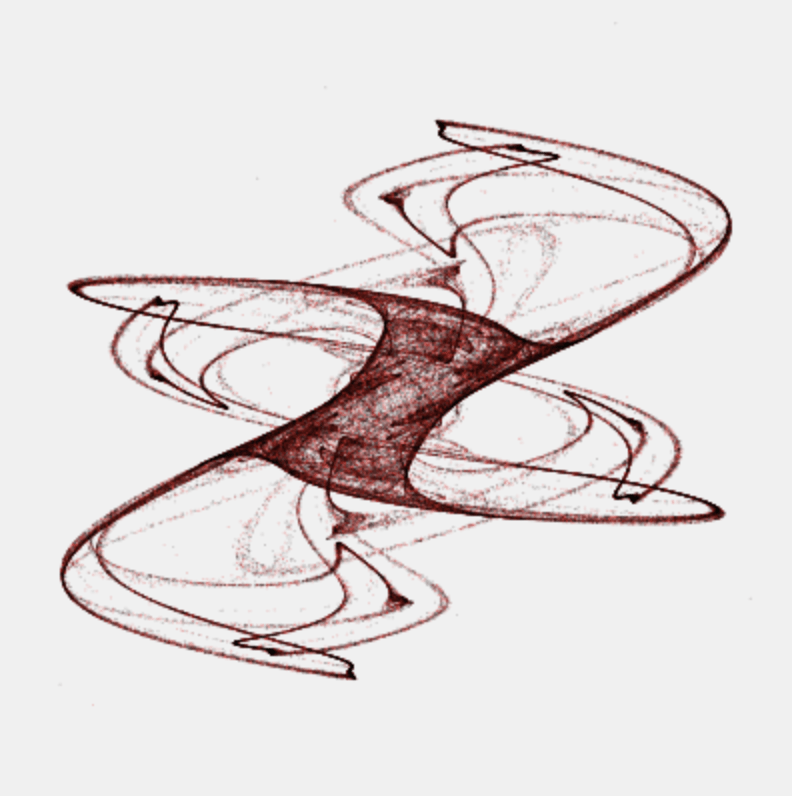

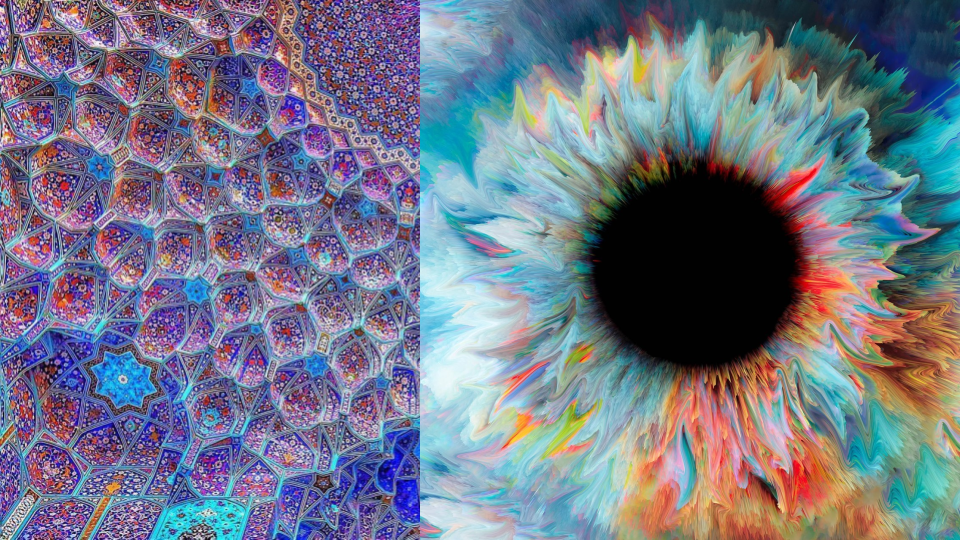

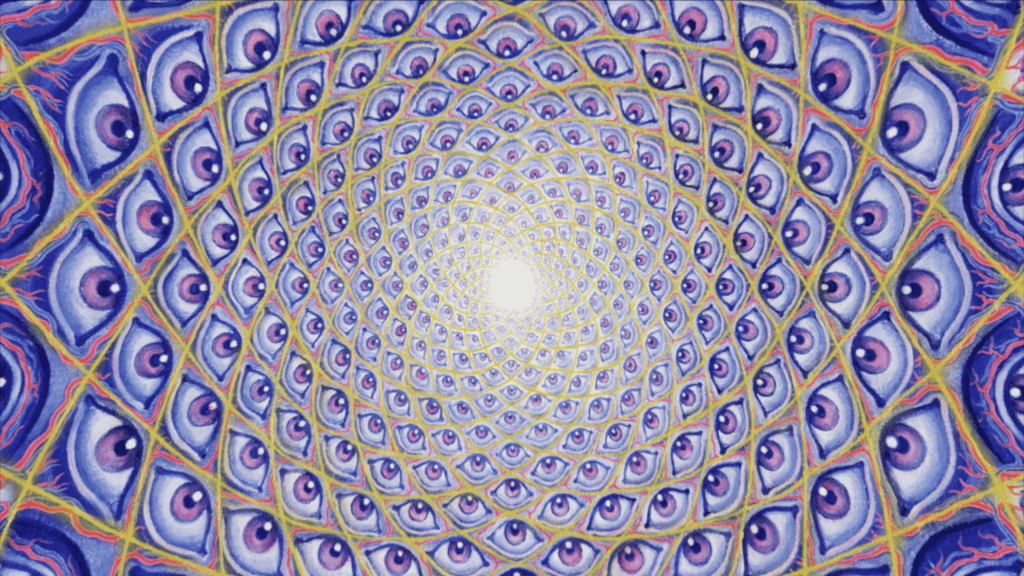

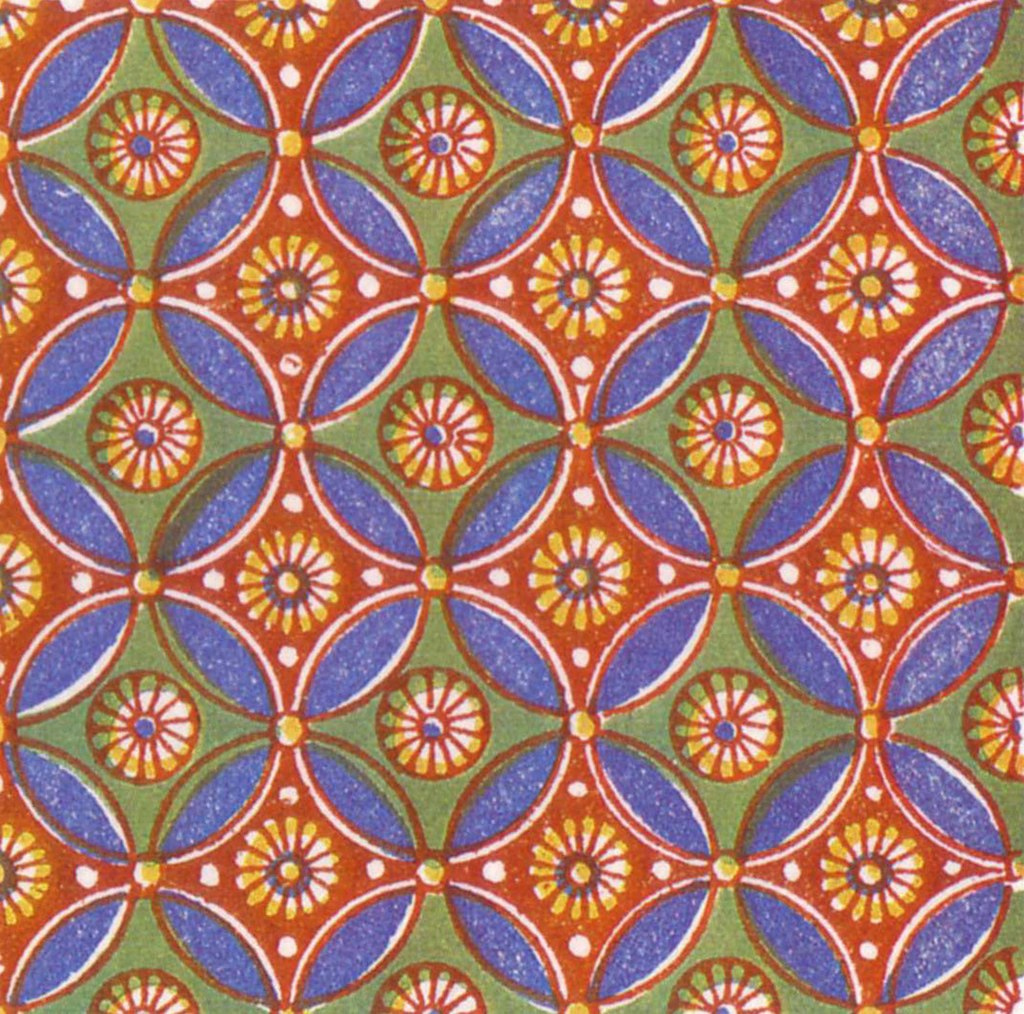

La idea del estructuralismo de la valencia, propone que lo que determina esta misma en cada experiencia es su estructura.Si nos fijamos, podemos relacionar la estructura de diferentes sensaciones con qué tan bien o mal se sienten, cualquiera que sea su contenido y forma. Las sensaciones placenteras tienden a tener un flujo ininterrumpido y simétrico, mientras que las desagradables, tienen operaciones de rompimiento de la simetría, como reflexiones y torceduras.

Así de la mano del estructuralismo de la valencia, viene la teoría de la simetría de la valencia, las simetrías están detrás de muchas cosas en la física y está de acuerdo con aquello que podemos experimentar que estas mismas estén detras de la valencia.

Hay 17 grupos del papel pintado.

Un buen ejemplo es el dolor corporal vs un masaje, pero se puede dar una argumentación más amplia, la teoría de la simetría de la valencia se puede explorar desde una gran cantidad de perspectivas, por ejemplo neurológicas y desde la física.

El verdadero valor está en la valencia.

Como mencionaba, aquello que percibimos como si fueran los objetos de nuestro interés no son directamente estos mismos sino una representación dentro de nuestras cabezas.

Lo que sentimos como el valor de estos mismos depende de la estructura de aquella representación.

Así para algún niño, un payaso se sentirá como una aproximación a la encarnación misma del mal mientras que un chocolate a estar hecho de partículas de delicia pura. Mientras que todo este valor sentido está en realidad codificado en su estructura

La valencia de estos objetos genera que tengamos intenciones frente a ellos, por eso los conocemos como objetos intencionales.

A veces se los conoce como los reinos de las fijaciones

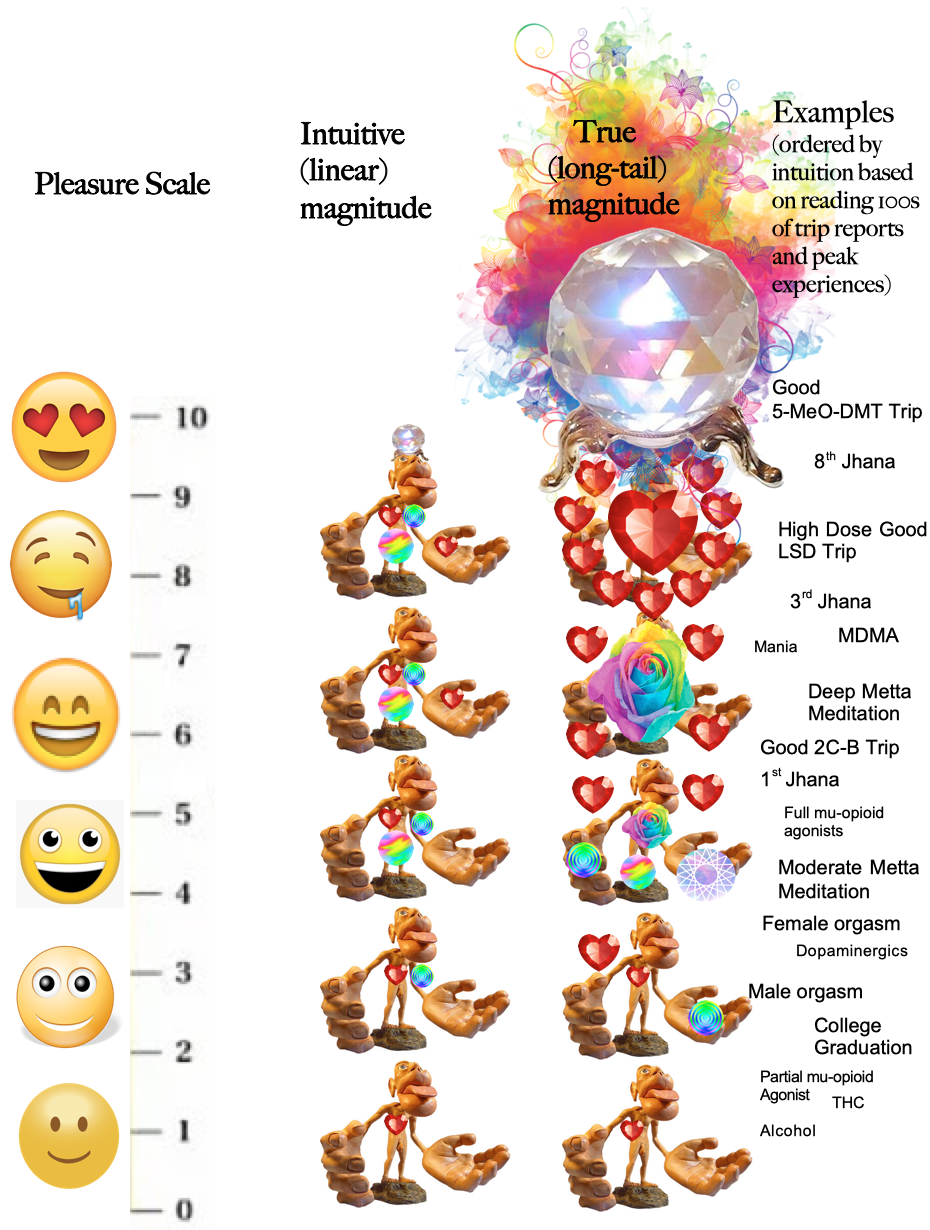

El verdadero valor está en la valencia, podemos tener valor sin que este esté venga junto a objetos intencionales, existe, por ejemplo, una gran cantidad de estados de meditación donde esto sucede.

Por supuesto que mucho de lo que representamos como valioso es realmente necesario para vivir, para no sufrir y para tener aquellos hermosos estados de alta valencia, una muy gran parte de nuestra felicidad viene de tener una alimentación adecuada o de buenas relaciones sociales. Podemos encontrar formas nuevas de mirar este tipo de cosas.

Sin embargo hay objetos intencionales que prácticamente en consenso podemos ver como ilusorios, por ejemplo los de muchos estados de manía, o de psicosis. Si después analizamos con una epistemología apropiada muchas otras creencias humanas, vemos que tienen un estatus parecido.

Lo que tienen los objetos intencionales es una especie de tiranía sobre nuestras experiencias, que nos lleva a gastar, o deberíamos decir desperdiciar recursos en cosas que no son más que apariencias en nuestra pequeña representación del verdadero universo.

El (des)valor existe verdadera e independiente de «quien» lo experimente.

Más concorde a la realidad, está entender lo que existe como experiencias que hacen parte del campo universal (¿»quién» o «qué» somos?).

Si paramos de dejarnos llevar por estas apariencias…

las apariencias van muy lejos, dependiendo de la intensidad «del nivel de energía» en cada experiencia.

…y reconocemos que el bienestar está en la estructura, podemos encontrar una forma mucho más efectiva de mejorarlo.

Las apariencias tienden a hacer que nos aferremos a ellas y esto nos hace sufrir. Esto mismo puede ser entendido como una forma de expresar lo que se expresa en el camino a la liberación del sufrimiento budista.

-

Today I am going to talk about what value is and what is valuable.

Darwinian life on earth tends in many cases to be a very cruel process, where there are large amounts of suffering.

What does it feel like to be different animals?

Most likely the lion thinks about what to eat.

Does it feel like freedom to fly like a bird?

Whales most likely live in a world built on their echolocation.

Some animals live terrified and escaping, others are suffering intensely.

Human beings share much with other animals and at the same time we have an intellectual and rational side.

All animals have tendencies or fixations and these move us.

But there are contradictions between what different animals consider valuable, different «observers» «observe» (note the quotation marks, left there to leave a questioning about «what» observers are) the same situation in different ways. So…

…Is there really something valuable?.

From the perspective of the agonizing animal, its suffering is truly and intensely horrible, regardless of what any other being may think, in the same way, the deep ecstasy of a jhana is real.

In a way it can be argued that al the suffering of the universe is in truth, «ours» (or is ours «theirs»/»his»/»hers»? Is there really a self?).

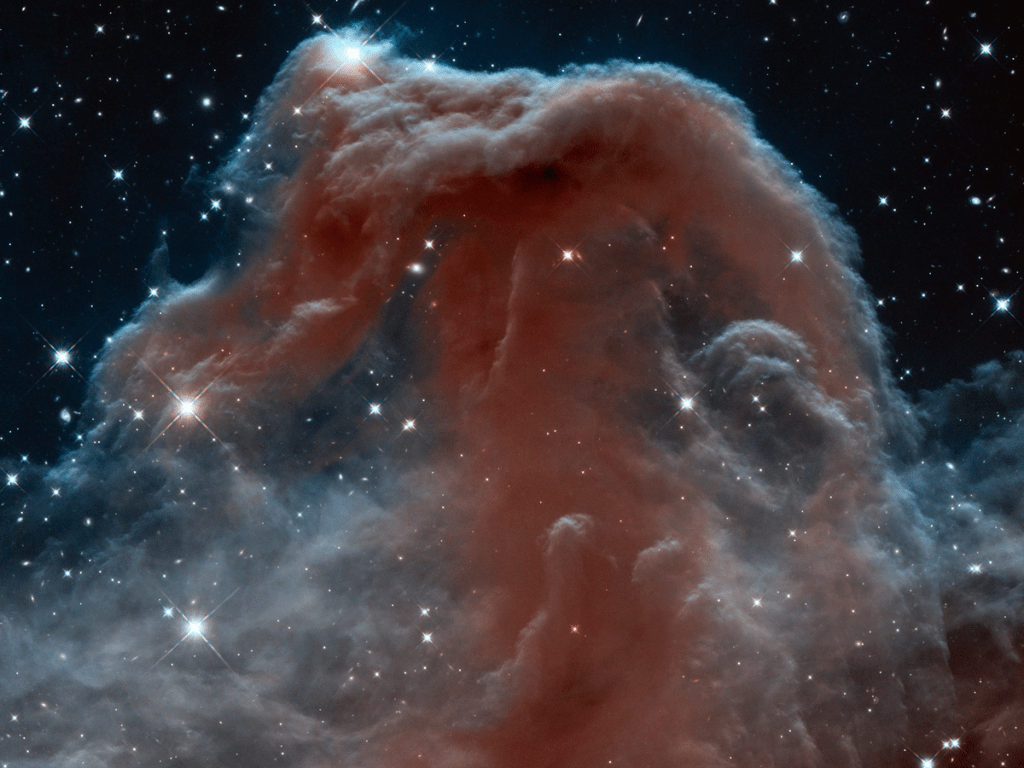

Physicists have taught us to see «thing(s)» as field(s).

And what is the value in these experiences?

We humans have tried to understand the nature of pleasure and pain in many ways, we have related it, for example, to the activation of different areas of the brain, the ventral tegmental area for pleasure and the cingulate gyrus for pain are some of those that we have found.

It has been noted that when we experience things that induce feelings of well-being or discomfort, these areas are activated.

In Geshwind syndrome, a type of temporal lobe epilepsy, people have extremely deep and beautiful experiences, which tend to lead to hypergraphia, hyperreligiosity and deep spiritual experiences. All this explained by abnormal neuronal activity that tends to be attributed to other causes.

To properly understand the world, one of the most relevant ideas is that of indirect realism of perception. That which we experience we experience is not directly the external world (cf. naive realism), but rather a representation or simulation within our heads, a kind of diorama based on the external world. To form an image of this concept, we can imagine a kind of bubble made of qualia that takes the form of a world (I discuss this concept in more detail here). Indirect realism of valence also applies to our experience; the things we perceive as valuable are not directly valuable, but rather they have a valence.

Thus our representations have appearances that do not necessarily reflect the true nature of external world. That’s why we could say, Buddhists speak of a cyclical existence in realms of fixations, which form a fictitious appearance of reality from within, and that’s why one of the three marks of existence according to them is unsatisfactoriness.

Each experience has a certain valence, there is positive valence, such as joy, negative as that of pain, there is mixed, we can feel positive and negative valence at the same time, or there is neutral.

Valence is usually interpreted in ways other to «this is valence» by our experience, even though whats actually happening is that there are representations, which have different valences, it is often thought that what activates different states of valence is directly good or bad.

The idea of valence structuralism proposes that what determines it in each experience is its structure.

If we look closely, we can relate the structure of different sensations to how well or badly they feel, whatever their content and form. Pleasant sensations tend to have an uninterrupted and symmetrical flow, while unpleasant ones have symmetry breaking operations, such as reflections and twists.

Thus, hand in hand with structuralism of valence, comes the symmetry theory of valence, symmetries are behind many things in physics and it is in agreement with what we can experience that these same are behind valence.

There are 17 wallpaper groups.

A good example is body pain vs a massage, but a broader argumentation can be given, the symmetry theory of valence can be explored from a large number of perspectives, for example neurological and from physics.

True value is in valence.

As I was mentioning, what we perceive as if they were the objects of our interest are not directly these same but a representation within our heads.

What we feel as the value of these same depends on the structure of that representation.

So for some child, a clown will feel like an approximation to the very incarnation of evil while a chocolate is made of particles of pure delight. While all this felt value is actually encoded in its structure

The valence of these objects generates that we have intentions towards them, that is why we know them as intentional objects.

Sometimes they are known as the realms of fixations.

True value is in valence, we can have value without this coming bound to intentional objects, there is, for example, a large number of meditation states where this happens.

Of course, much of what we represent as valuable is really necessary to live, to cooperate, to not suffer and to have those beautiful states of high valence, a very large part of our happiness comes from having an adequate diet or good social relationships, for instance. We can find new ways to look at these kinds of things.

However, there are intentional objects that practically in consensus we can see as illusory, for example those of many states of mania, or psychosis. If we then analyze with an appropriate epistemology many other human beliefs, we see that they have a similar status.

What intentional objects have is a kind of tyranny over our experiences, which leads us to spend, or should we say waste resources on things that are nothing more than appearances in our small representation of the true universe.

(dis)value exists truly and independently of «who» experiences it.

More in agreement with reality, is to understand what exists as experiences that are part of the universal field («who» or «what» are we?).

If we stop letting ourselves be carried away by these appearances…

appearances go very far, depending on the intensity «of the energy level» in each experience.

…and we recognize that well-being is in structure, we can find a much more effective way to improve it. Appearances tend to make us latch onto them, and that makes us suffer. This can be understood as a way to express what is also expressed in the buddhist path to liberation.

-

La forma en que la mayoría de los humanos clasifican lo que importa generalmente no sigue lo que realmente lo hace. Nuestra programación predeterminada está optimizada para rastrear cosas que nos ayudaron a reproducirnos y sobrevivir en nuestro paisaje ancestral y para «pintarlas» de manera que estas se sintieran como si estas fueran las cosas que realmente nos importasen. También tienden a sentirse como si estuviéramos en contacto directo con la cosa externa y su esencia. Todo esto en realidad no es cierto, nuestras experiencias de las cosas son en realidad representaciones internas isomórficas a lo que está fuera nuestro. Cada vez que ves algo fuera de ti, la luz que refleja llega a tu retina, lo que activa tu nervio óptico, que envía señales a tu cerebro donde se hace una representación que es lo que en realidad estás experimentando. Lo mismo ocurre con todas las demás sensaciones del «mundo exterior». Muchas personas dirían si se les pregunta, que esto es obvio, pero muchas veces no lo entienden realmente, o no llevan esta línea de razonamiento lo suficientemente lejos como para que empiece a afectar la forma en que actúan, o la siguen solo parcialmente de maneras que los llevan a concluir que nada realmente importa, actuando así también de manera irresponsable.

Nuestro cerebro hace una representación/simulación de la realidad, eso es en lo que «vivimos»/somos, de cartoon epistemology.

Las cosas (o mejor dicho, las experiencias) fuera del bolsillo que somos sí importan, y mucho. De la misma manera que las partículas pueden tener cargas o la materia tiene diferentes temperaturas, cada experiencia tiene una característica que hace que se sienta bien, mal o de una manera neutral, esa característica es la valencia, la valencia es lo que construye el eje placer-dolor. El hermoso olor de las fresas generalmente tiene una valencia positiva, lo mismo que la alegría, mientras que el dolor o el temor existencial generalmente tienen una valencia negativa. Aunque alguien podría decir que la experiencia de ver, por ejemplo, como sucede un evento particular es subjetiva y puede ser diferente dependiendo de a quien se le pregunte, o la experiencia de escuchar la misma canción, o ver el mismo objeto puede ser mejor o peor para diferentes personas, haciendo así que el valor sea relativo, yo argumentaría que esa conclusión es solo el resultado de intentar medir el valor de manera incorrecta. El valor en realidad reside en las experiencias, tu representación del holocausto muy probablemente tiene un tono negativo, mientras que la de alguien que lo apoyó puede tener uno positivo, pero esas opiniones no cambian las experiencias de quienes lo vivieron, su sufrimiento sigue siendo malo. También podemos notar que lo que hace que diferentes representaciones del mismo fenómeno se sientan de mejor o peor manera es la estructura de esas experiencias, y así, si una canción te pareció hermosa un día y al siguiente horrible, esto en realidad es causado por diferencias en las formas y estructuras de estas representaciones (probablemente lo que determina qué tan buenas o malas son esas estructuras son sus niveles de consonancia y disonancia). La valencia es real, las experiencias horribles son realmente, verdaderamente horribles y las hermosas son realmente hermosas. Esto se hace evidente para quien se ha roto una pierna, para quien sufre de dolor crónico, o para quien está teniendo una experiencia increíblemente intensa y llena de amor con MDMA. Otra forma en la que puedes pensar sobre esto es dándote cuenta de que tu momento de experiencia actual es «lo que es» y se siente tan bien, mal o neutral como se sienta, independiente de las opiniones que alguien más pueda tener sobre este, lo mismo aplica para todos los demás momentos de experiencia del universo.

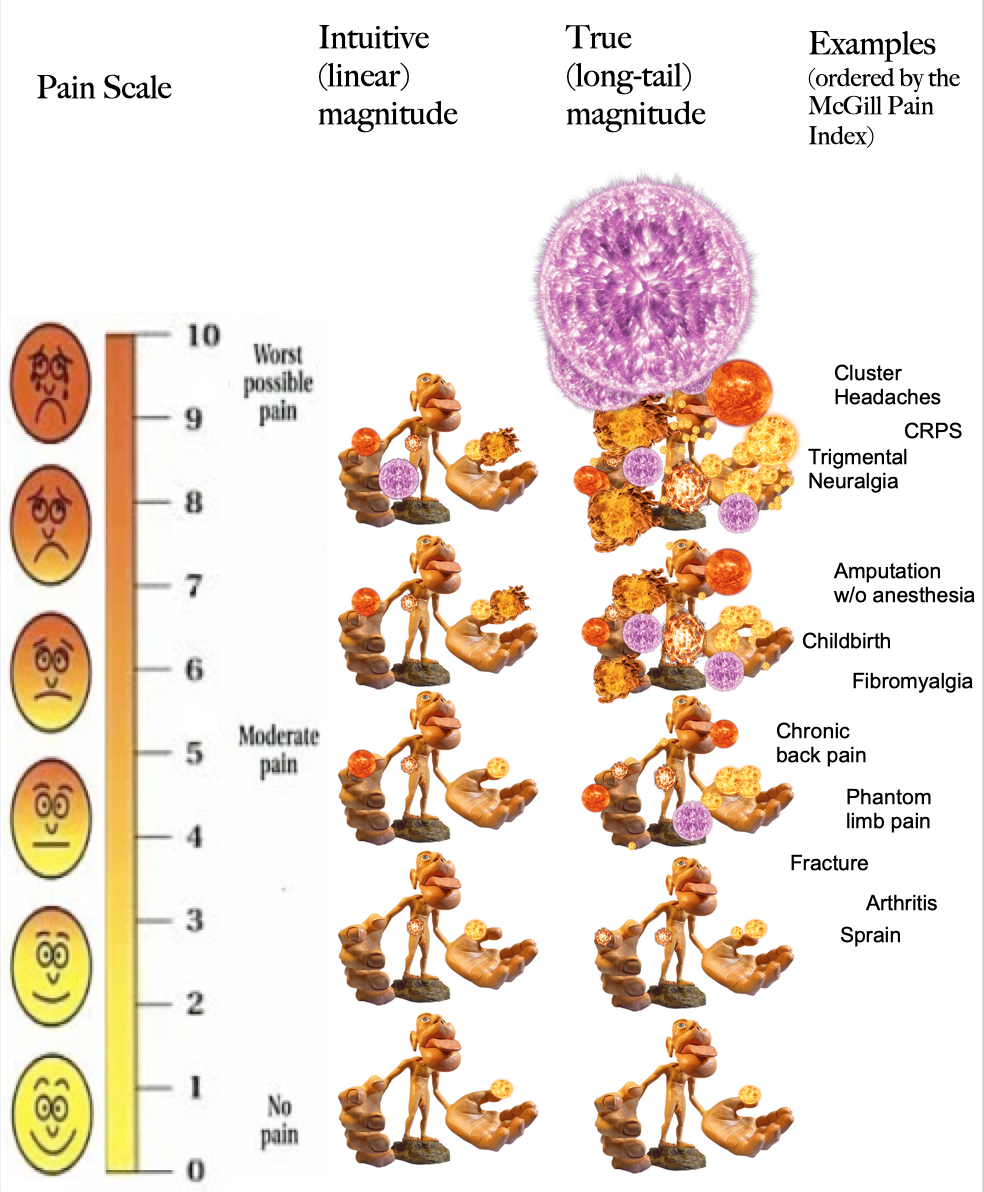

Creo que deberíamos actuar con extrema responsabilidad hacia esos momentos de experiencia con valencia tan intensa, el que no nos importe tiende a doler después, mucho. La mayoría de las personas reconocerán que conducir borracho es bastante tonto e irresponsable, lo mismo que enfrentarse a un ladrón con un cuchillo cuando no tienes uno, pero creo que deberíamos aplicar ese cuidado y seriedad sobria hacia muchas otras cosas, tomando también en consideración el hecho de que las peores y mejores experiencias tienen exponencialmente más valor que las cosas que usualmente experimentamos, como Andrés Gómez Emilsson escribe en Logarithmic Scales of Pleasure and Pain: Rating, Ranking, and Comparing Peak Experiences Suggest the Existence of Long Tails for Bliss and Suffering.

Aunque podamos imaginar que las experiencias crecen en intensidad linealmente, hay muchas razones para creer que en realidad lo hacen exponencialmente.

Para alguien que vivió hace 20,000 años, muchas cosas que nos importan hoy, digamos nuestras calificaciones en la escuela o las interacciones a través de las redes sociales, probablemente serían extremadamente extrañas e inesperadas. Yo diría que, después de tomar una mirada sobria y seria en la naturaleza real del valor y dejar que eso actualice honestamente las cosas que priorizamos y las formas en que actuamos, también terminamos con una forma bastante diferente de ver el mundo y sobre lo que deberíamos hacer, la cual puede ser bastante inesperada. Ahora comenzamos a pasar mucho tiempo tratando de encontrar formas de abortar cefaleas en racimos, maneras de tratar mejor el dolor crónico, o comenzamos a ver las cosas increíble y extremadamente horribles que suceden en la industria ganadera a través de una perspectiva diferente a la humana usual en el que solo parece algo lejano que está, mediante alguna lógica dudosa, justificado, incluso comenzamos a dudar de las formas en las que deberíamos actuar ante la existencia del sufrimiento de los animales salvajes, y comenzamos a preocuparnos mucho más por intentar que nuestro futuro vaya en buenas direcciones, entre muchas otras cosas.

Imagina que hubiera alguien que tuviera un botón que activara una máquina que le cortaría el dedo 10 minutos después de presionarlo, pero tuviera un poco de diversión al presionarlo y eligiera hacerlo voluntariamente, claramente no muy inteligente, ¿quién en su sano juicio lo presionaría? Yo argumentaría, sin embargo, que esta categoría de problemas también incluye los tipos de cosas mencionadas anteriormente, la gente toma decisiones basadas en sus deseos inmediatos y no considera el efecto que eso puede tener en otros lugares/momentos.

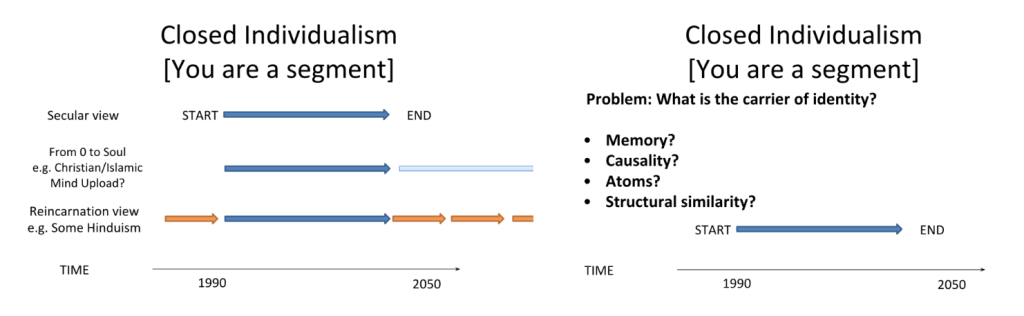

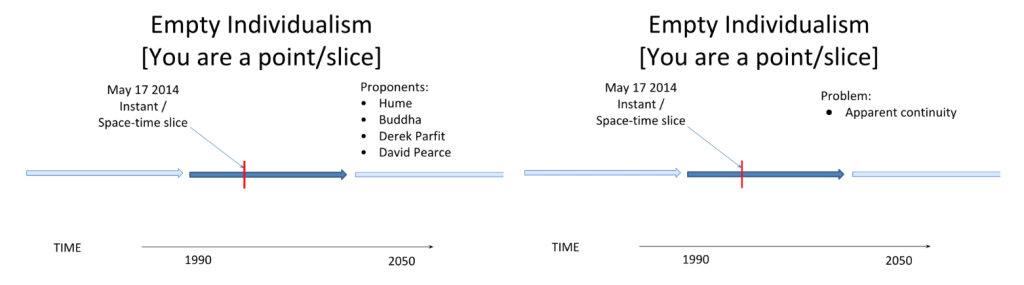

Una perspectiva importante para agregar a esto es de la identidad personal. ¿Cómo podemos estar tan seguros de que somos un ser separado e independiente que sobrevive a través del tiempo? ¿qué es lo que cargaría nuestra identidad a través del tiempo? ¿nuestros recuerdos? no son agujeros de gusano hacia el pasado, solo son formas que toma nuestro cerebro que hacen que representaciones de cosas que nos han sucedido reaparezcan en nuestra experiencia, además, si alguien tuviera los mismos recuerdos, ¿serían automáticamente la misma entidad que tú en otro lugar? ¿por qué? si perdieras tus recuerdos, ¿de repente te convertirías en una entidad diferente?, los recuerdos no son entidades fundamentales, solo son estructuras particulares que toma nuestro cerebro, nuestros átomos también están cambiando todo el tiempo, lo mismo ocurre con la forma de nuestro cuerpo (que como decía, no es fundamental, dos cuadrados con el mismo ancho y longitud no son el mismo cuadrado solo porque su forma sea compartida), yo argumentaría que no es posible encontrar tal portador constante «solo tuyo» de identidad, y que si estamos dispuestos a aceptar que lo que somos sobrevive con el tiempo, tendríamos que también aceptar que ese portador de identidad es el mismo para todos los seres, tus átomos alguna vez estuvieron dentro de una estrella y alguna vez pudieron haber pertenecido a otro animal, no hay nada que haga lo que te conforma «solo tuyo» y separado de lo demás, también está la perspectiva que ve al universo como un campo único, que tiene muchos segmentos como el que somos, entre muchos otros argumentos que no mencionaré aquí. Deberíamos considerar seriamente la idea de que en el fondo somos solo un ser, o al menos que no somos realmente individuos de la manera que usualmente asumimos que somos, aunque estas visiones inusuales sobre la identidad personal puedan parecer solo cosas esotéricas que la gente ve revelada en psicodélicos y no algo proveniente de un entendimiento científico y sobrio, la idea del individualismo abierto «todos somos uno» ha sido defendida y considerada por muchos pensadores famosos cuyo pensamiento usualmente no consideramos solo tonterías (por supuesto esto no es necesariamente un argumento para darle credibilidad inmediatamente pero vale la pena mencionarlo), como Arthur Schopenhauer, Erwin Schrödinger y Freeman Dyson entre muchos otros, y creo que después de pensar profundamente sobre el tema, encaja muy bien en una forma científica racionalista de ver la realidad.

Se puede argumentar que el sufrimiento de un cerdo en un matadero, o de alguien teniendo una cefalea en racimos es en realidad el nuestro, entonces ¿por qué hacernos/dejarnos dejar sufrir? ¿por qué no deberíamos actuar con la misma responsabilidad que ya damos a muchas cosas, para evitar que les pasen cosas malas a seres que probablemente son diferentes de nosotros de una manera ilusoria?. Además, incluso ignorando esta visión, puedes notar que todas las experiencias son igualmente reales y en última instancia solo expresiones del mismo universo, creo que es extremadamente difícil encontrar una razón por la cual tu experiencia de alguna manera sería más importante que el resto solo por ser tuya.

No deberíamos permitir que sigan ocurriendo cosas horribles, deberíamos actuar para reducirlas tanto como sea posible, y salvarnos.

-

The way most humans classify what matters usually doesn’t follow what actually does. Our default programming is optimized to track things which helped us reproduce and survive in our ancestral landscape and to «paint them» so that they felt as if they mattered, as if they were the things we actually cared about. They also tend to feel as if we were contacting the actual external thing and its essence. All of this actually isn’t true, our experiences of things are actually internal representations isomorphic to the stuff outside of us. Whenever you see something outside of you, the light it reflects hits your retina, which activates your optic nerve, which sends signals to your brain where a representation is made which is actually what you are experiencing. The same for all other sensations of the «external world». A lot of people say, when asked, that this is obvious, but at many times they don’t necessarily actually get it, or they don’t take that line of reasoning far enough so that it starts affecting the way they act, or they follow it only partially in ways which make them conclude that nothing actually matters, thus also acting in irresponsible ways.

Our brain makes a representation/simulation of reality, thats what we «live» in/are, from cartoon epistemology.

Things (or rather should I say experiences) in the outside of the pocket we are do matter though, a lot. The same way that particles may have charges or matter has different temperatures, I would argue that each experience has a characteristic that makes it feel good, bad or neutral, that characteristic is valence, valence is what builds the pleasure pain-axis. The beautiful smell of strawberries usually has a high valence, the same for joy, while grief or existential dread usually have negative valence, even though someone may say that the experience of seeing, for instance, a particular event happening is subjective and can be different depending on who you ask, or the experience of listening to the same song, or seeing the same object may be better or worse for different persons, making value thus relative, I would argue that that conclusion is just a result of trying to measure value in the wrong way. Value actually lies on experiences, your representation of the holocaust most likely have a negative tone, while the one of someone who supported it may have a positive one, but those opinions don’t change the experiences of those who lived through it, their suffering is still bad. Also we can notice that what makes different representations of the same phenomenon be felt in better or worse ways is the structure of those experiences, and so, if you found a song beautiful one day and a the next one horrible, that actually is caused by the representation of it having different shapes and structures (probably what determines how good or bad those structures are is their levels of consonance and dissonance). Valence is real, horrible experiences are actually, truly horrible and beautiful ones are actually beautiful. This becomes clear to whoever has broken their leg, or to whoever suffers from chronic pain, or to whoever is having an incredible and almost unbelievably intensely love filled experience on MDMA. Another way you could think about this is by noticing that your current moment of experience is «what it is», and is as good, bad or neutral as it is, independent of whatever opinions someone else might hold about it, the same applies for all other moments of experience.

I think we should act extremely responsibly towards those heavily valenced moments of experience, not caring tends to hurt later, a lot. Most people will recognize that driving drunk is really dumb and irresponsible, the same for fighting against a mugger who has a knife when you don’t, but I think we should apply that sober seriousness and carefulness towards many other things, also taking into consideration the fact that the worst and best things have exponentially more (dis)value than the things we usually experience, as Andrés Gómez Emilsson writes in Logarithmic Scales of Pleasure and Pain: Rating, Ranking, and Comparing Peak Experiences Suggest the Existence of Long Tails for Bliss and Suffering.

Fven though we may imagine experiences experiences grow in intensity linearly, there are many reasons to believe that they actually do so exponentially.

For someone living 20,000 years ago, many things we care about today, say our grades at school or interactions through social media, would probably be extremely alien and unexpected. I would argue that after taking a sober and serious look into the actual nature of value and letting that honestly update the things we prioritize and ways in which we act, one also ends up with a pretty different way of looking at the world and about what one should do, which can be pretty unexpected. Now one starts to spend a lot of time trying to find ways in which to abort cluster headaches, ways in which to better treat chronic pain, or one starts seeing the incredibly and extremely horrible things that happen in factory farming through a lens different from the usual human one in which it just looks like something far away that is through some sketchy logic, justified, we even start doubting the ways in which we should act upon the existence of wild animal suffering, and we start to care a lot more about trying to make our future go in good ways, amongst many other things.

Imagine there was someone who had a button which activated a machine that would cut his finger 10 minutes after pressing it but they had a tiny bit of fun while pressing it and they willingly chose to press it, clearly not very smart, who in their right mind would press that? I would argue though that this category of problems also includes the type of things mentioned above, people take decisions based on their immediate desires and not considering the effect that may have on other places/moments.

An important view to add into this is the lens from personal identity. How can we be so sure that we are an separate and independent self that survives over time? what is that which would carry our identity over time? our memories? they are not wormholes into the past, only shapes our brain takes which make representations of things that have happened to us reappear in our experience, plus if someone had the same memories would they automatically be the same entity as you somewhere else? why? if you lost your memories would you suddenly become a different entity? memories aren’t fundamental entities, they are just particular structures in our brain, our atoms are also changing all the time, the same for the shapes of our brain/body (which, as I said, aren’t actually fundamental, two squares with the same width and height aren’t the same entity despite sharing their shape), I would argue that it is not possible to find such a constant «only yours» carrier of identity, and that if we are willing to accept that what we are survives over time, we’d have to also accept that that carrier of identity is the same for all beings, (your atoms once were inside of a star and once may have belonged to another animal, the same for everything that forms you), also there’s the view that sees the universe as one field, which has many segments like the one we are, amongst many other arguments that I won’t mention here. Arguably we should seriously consider the idea that we are actually deep down only one being, or at least that we aren’t actually individuals in the way we usually assume we are, although this unusual views over personal identity may seem like just esoteric stuff that you see revealed on psychedelics and not something out of a scientific, sober understanding, the view of open individualism «we are all one» has been defended by many famous thinkers whose thinking we wouldn’t consider just woo (off course this isn’t necessarily an argument to immediately give it credibility but it’s worth noting), like Arthur Schopenhauer, Erwin Schrödinger and Freeman Dyson amongst many others, and I think that after deeply thinking about the subject, it fits very well into a scientific rationalistic way of looking at reality.

It can be argued that the suffering of a pig in a slaughterhouse, or of someone having a cluster headache is actually our own, so why make/let ourselves suffer? why shouldn’t we act with the same responsibility we already give many things, to avoid bad stuff happening to beings that probably are only illusorily different from us?. Also, even ignoring this view you can notice that all experiences are equally real and ultimately just expressions of the same universe, I think it’s extremely hard to find a reason why your experience would somehow be more important than the rest just because of it being yours.

I’d say that we should not let horrible stuff keep happening, we should act to reduce it as much as it is possible, and save ourselves.